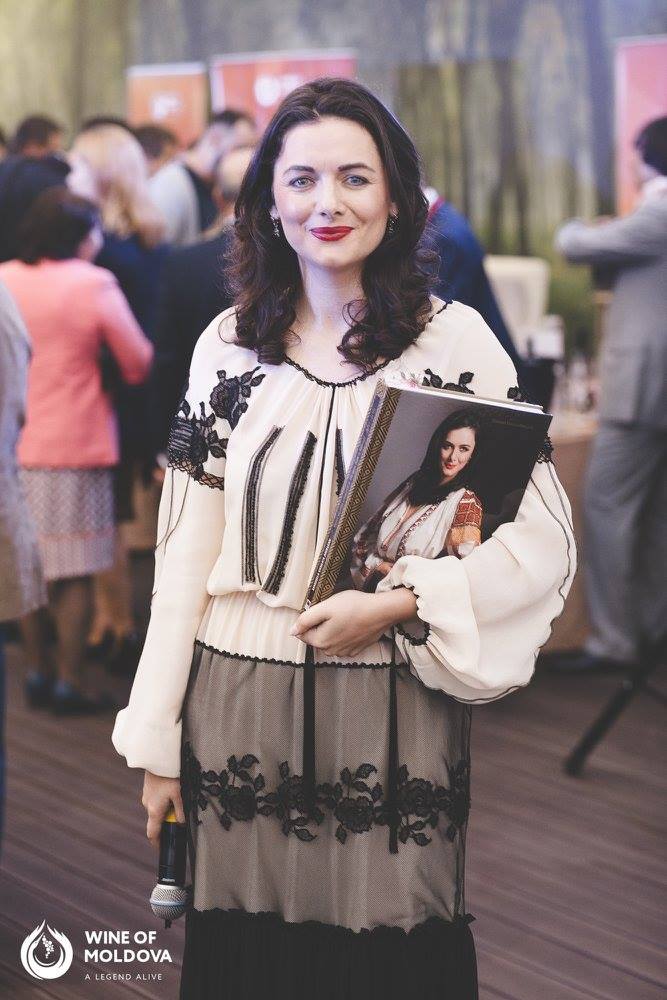

Marinela Ardelean: “Without the involvement of the state there is no true possibility of promoting Romanian wines as a whole, – as a brand itself and as part of the national brand”

Marinela Ardelean has earned the reputation of a bright leader in the world of wine, advocating for a bright future for Romanian wines. Her courage, dedication, and unwavering commitment to defending the interests of Romanian winemaking have earned her comparisons to Joan of Arc, and she could be proclaimed as the Maid of Transylvania. A Drinks+ columnist asked Ms. Ardelean questions to shed light on her struggles today and the future of Romania’s wine community.

Romania is a fascinating wine country full of paradoxes. While grape cultivation dates back to the sixth millennium BC, its modern wine industry is only about 30 years old. Political and cultural upheavals, particularly the Soviet occupation, negatively impacted wine production. After the fall of the regime, the industry was reprivatized and received significant foreign investments, mainly from Italian, Austrian, and British companies. Since 2013, Romania has received about 45 million euros ($51 million) annually from the EU for its wine industry, most of which was used for replanting vineyards. Today, Romania boasts some of the largest and best-maintained vineyards in Eastern Europe. However, there are still instances of descendants of former vineyard owners fighting to reclaim land seized nearly a century ago by the communist regime. Do you know of any successful or ongoing restitution cases?

M.A.: There have been, of course, several successful restitutions, some involving larger than boutique-winery levels. I would mention the Persu-Eminescu family, who had 40 hectares and merged with the 45-hectare Franco-Romanian Estates to become one of the most successful eco / bio wines producers. There are also others, mostly with surfaces ranging from 5 to 20 hectares, there are wineries that started small, with a few hectares, and then continued to acquire neighboring plots and kept developing over the years. However, most of the large wineries were formed either through the privatization of former state-owned farms or through direct foreign investments. Although the large state-owned farms that were privatized at the end of the 1990s and the beginning of 2000 had a lot to work to upgrade their technology, replant the vineyards and produce higher-quality wines, most of them became successful – I should at least mention Jidvei, Cotnari and Recas, adding that Cramele Recas, Romania’s largest exporter to UK, started with some 600 hectares and now owns over 1,200. So, there are success stories at all levels, regardless of the way the wineries were born.

According to statistics, in 2023, Romania produced approximately 4.6 million hectoliters of wine. In 2021, the country produced 530 million liters of wine, comparable to the combined production of Hungary and Austria. Currently, Romania ranks sixth in the EU and 12th in the world in wine production. However, only 7 percent of the wine produced in 2021 was exported. Annually, Romania imports about 65 million euros worth of foreign wines while exporting only 35 million euros worth. For comparison, Romania produces more wine than New Zealand, Greece, and Hungary but exports less than Denmark, Austria, Slovakia, or Bulgaria. How can this phenomenon be explained?

М.А.: So far, the domestic consumption was quite enough to absorb the production, as well as some 15-20% imported wines, so exports were less of a priority for many producers. More than this, there seems to be a general reticence among smaller producers in forming associations and cooperatives that would allow them to present their offer abroad. It is, most probably, a reminiscence of the hatred towards the forced association into state farms during the Communist era. But I truly hope this is a trauma we shall soon surpass, because wine export becomes increasingly important, as new wineries appear and more vineyards come to maturity.

So the Romanian wine sells well on the domestic market due to the quality of local wine and a patriotic trend among young consumers. Producers focus on developing the local market rather than other markets. In your opinion, how crucial is the export vector for the promotion strategy of a relatively new wine-producing country, such as Romania or Ukraine? How can one maintain a balance so that not all of a winery’s budget is spent on export efforts, while still developing the domestic market with enough funds for participation in national exhibitions, media campaigns, and promotions in local establishments? In general, what is the correct strategy — first gaining recognition in foreign markets and then conquering the domestic market, or vice versa?

M.A.: The annual business figures of small wineries clearly don’t allow them to take part in major international wine fairs or support significant international media campaigns. So selling locally or on the general Romanian market is at hand.

On the other hand, I noticed that being listed in a Michelin-starred restaurant doesn’t necessarily makes a Romanian wine more popular on the domestic market. On the other hand, major awards, such as Revelation of the Concours Mondial de Bruxelles or a Grand Gold Medal at Mundus Vini almost always increase the demand, from both distribution companies / restaurants and private clients. Since the participation in such contests is a lot more affordable, I think this would be a first step for small wineries – gaining that recognition to add an impulse to locale sales, capitalize on that and then make a move towards export.

According to our observations, the key weakness of the wine industry in Romania is the thousands of landowners who cultivate tiny plots of land, often no larger than a swimming pool, making it difficult to run a profitable business effectively. Only a few own large areas. For instance, during the WTA award ceremony in London, you introduced the international wine community to market leaders like Jidvei. In 2022, the leading company in the Romanian wine industry, by annual revenue and net profit, was Cramele Recas; Jidvei and Zarea ranked second and third, each with a revenue of over 160 million Romanian lei. Is there an issue with such a disparity between vineyard owners? Does everyone follow their own path to success?

M.A.: I would say success is defined by each one’s measure. We have wineries with 60-70 hectares selling their wines for 100-350 euros per bottle. We have wineries that had to struggle and convince the foreign owners that they can produce high-quality wines, asking to be at least allowed to produce experiments for the domestic market, even though the owners were rather interested in producing entry-level, affordable wines for foreign markets – and this is still the backbone of their business. As said before, the main difference is in how these wineries were born – all the large ones are privatized former state farms, the medium ones (150-700 hectares) come from direct foreign investments, while the inherited plots that turned into wineries are usually small vineyards, from one to 40 hectares.

So despite all the obstacles and features of the market, Romanian wine is now exported to approximately 40 markets. According to 2021 data, the USA, Canada, Switzerland, and Japan are among the top destinations. What are the current trends with export vectors? It has been suggested that small Romanian producers, unable to compete with volume leaders, should focus more on trading in the UK. Some, as we understand, are also targeting the German market. Additionally, e-commerce seems to be working well for exporting Romanian wines. Could you comment on this situation and name the five most promising markets for Romanian wine?

M.A.: I believe that more producers, not only the small ones, should capitalize on the breakthrough made by Cramele Recas on the UK market, but maybe it is not the right moment now. For the time being, Romanian wines in the UK are still lower-shelves, entry-level wines, but that is where the trade begins. In time, I am sure you’ll see Romanian wines climbing to higher shelves, as well as in restaurants. For many producers, I believe the German market should be a focus in the near future, given its size and the similarities in taste. Also, my feeling is that Scandinavian countries were overlooked, because of the state monopoly in some cases, but the relative success on the Canadian market, also a monopoly, should be a signal that these countries are approachable. There is a growing trend in exports towards Belgium and I know there is a significant interest in Romanian wines coming from Poland, which is interesting, due to size, average income and consumption habits.

Usually, such kind of organizations as Wines of… for example, act as the leading export body. What are the features of this structure in Romania? In your opinion, how should the industry ideally be coordinated at the national level? Should it start with an export plan and participation in international exhibitions? Who should be responsible for organizing invitations for buyers or the press to visit the country? Is decentralization more effective in today’s context?

M.A.: There are two major organizations that gather producers – APEV (The Wine Producers and Exporters Association) and ONIV (The Vine and Wine Interprofessional National Organization), as well as a few smaller regional or national associations. This is one of the cases where I think decentralization has failed. I think we need a strong private-state partnership, without the involvement of the state there is no true possibility of promoting Romanian wines as a whole, as a brand itself and as part of the national brand. From accessing European funds to state co-financing, such an institution would unburden a lot of the expenses producers should make on their own. Also, it would be a credible host to invite traders, importers, influencers, journalists and so on.

On your point of view, how receptive is Romania to experimentation, and are global trends like orange or vegan wines prevalent and practiced? What progressive ideas are gaining popularity in the country?

M.A.: Fortunately, we have many young winemakers and winery owners, there are many producers who employ foreign consultants, so we’re pretty much in touch with all international trends. So we have carbonic maceration, skin maceration, eco, bio, natural, pet-nat, brut nature and even kosher wines. The amounts are correlated to the size of the wine lovers’ hardcore, though, so we’re not discussing high volumes yet, with some exceptions – orange wines seem to have a good start. But there are several hundreds of hectares producing bio and biodynamic wines, there are wineries partially or completely focused on using local wild yeasts in fermentation, so I’d say we’re updated and in trend(s).

Are there any harmful myths about Romanian wine that need to be addressed? For instance, in Great Britain, there was a perception that Romanian wine is cheap and ordinary, whereas in Hungary, Romanian winemakers have been more successful in selling premium wines. What challenges are currently relevant in this regard?

M.A.: Brexit and taxes make it difficult for Romanian relevant premium wines to be listed in the UK for the time being. Maybe shortcutting through importers who cater exclusively to restaurants is a chance to bring forth some of the better things Romania has to offer. So far, there have been attempts to list the wines in luxury stores and networks, some high-end restaurants already listed Romanian wines… It’s a long road. All the buyers who got to taste Romanian wines were delighted, but I guess it is still too much of a risk, without a communication campaign to back up imports.

As for Hungary – they have great wines, they have a very nationalistic market, and the imports are still a small fraction of the total volume. They would never settle for lower quality than what we currently export there. And I think the common Romanian and Hungarian history in Transylvania helps a lot. Let’s not forget that a Romanian winemaker, Balla Geza, is a professor there and was awarded winemaker of the year in Hungary, a few years back.

We had to meet the opinion that in some countries, Romanian wines made from local varieties sell better when the grape names are not displayed on the label, but instead adapted to suit different export markets. Some names that are difficult to pronounce can deter wine lovers. What advice do you give to your clients or partners in this regard?

M.A.: Learn how to pronounce! Well, I am joking, at least a bit, since that is impossible without efforts from Romanian promoters – and we’re back to who and how should handle this. I guess my advice is not to worry – you can start by calling Feteasca “phe-tess-kah” instead of “phe-teh-‘ass-kah”. Taste it and, if you love it, share it! We’ll help improve the pronunciation over time. I think adapting names to a brand or something easier to pronounce would not benefit the Romanian native grapes, nor their consumers, in the long run. Maybe put a phonetic translation on the label?

By the way, Romania did suffer from phylloxera, which led to the replacement of many local vines with French varieties. Are there any indigenous varieties left, and how many are there? Could you describe the most interesting profiles of whites and reds, based on your taste? Also, how popular are these indigenous varieties today, and how well have they adapted to climate change?

M.A.: There are about 127 local grapes, legally, but many were born in the past 70 years, in research institutes. I’d say there are about 20 or 30 old grapes remaining, of which less than 15 are spread enough to be produced in significant amounts. The Feteasca family – alba (white), regala (royal) and neagra (black) – is the backbone of local varieties, with several grapes native to Moldova – Grasa de Cotnari, Francusa, Busuioaca de Bohotin, Galbena de Odobesti, Plavaie, Zghihara, and to Transylvania – Mustoasa de Maderat, Cadarca, etc. Then we have Tamaioasa romaneasca, which is spread throughout the country and that has been growing here for thousands of years, although it was recently identified as genetically being Muscat au petit grains blancs, and Cramposie – which through popular and then scientific selection became Cramposie Selectionata. There are also a few grapes born rather recently – 30 to 70 years ago, which yield great results – Sarba, Novac, Negru de Dragasani and, recently, Alutus.

My hope is that winery owners and research institutes will unite their efforts to resurrect some of the old varieties, which are now only scarcely cultivated.

Caroline Gilby MW writes that there continues to be significant commercial demand for Pinot Gris and Pinot Noir, which serve as pathways for Romanian wines to reach consumers, such as through labels like ‘I Heart’, owned by Freixenet Copestick. Do you find this viewpoint discriminatory considering the rising popularity of local varieties worldwide?

M.A.: The inherited structure of vineyards, about two decades ago, included vast areas under Pinot Gris and Pinot Noir. Our winemakers were employing a rather traditional approach to Pinot Gris (modern influences led to labeling the wine Pinot Grigio) and of more modern styles for Pinot Noir. So both found enthusiastic consumers in the UK and cast some shadow over local varieties. But fashion is changing, for sure, even if in some cases it may take longer. Cramele Recas already successfully sells local varieties – despite the fact that many can’t pronounce it correctly.

Shall we discuss sales channels? There’s a belief that wine made from unfamiliar grape varieties or from lesser-known countries requires personal interaction for sales. Targeting upscale restaurants could be a strategy to penetrate foreign markets, where wines are often recommended by knowledgeable sommeliers familiar with Romanian wine history. However, in British restaurants, prices for such wines can reach £35-£40. How many consumers are willing to take that risk without prior knowledge? Wouldn’t it be more effective to start by placing wines on supermarket shelves, where wine enthusiasts can try them at a lower cost? Then, after gaining familiarity, they might order them at restaurants. What’s your take on this approach? Could it be a better path for small winemakers, who may find the conditions of traders in the UK challenging despite interest from experts in the market?

M.A.: We already approached the subject, so now we’re coming to a conclusion. I believe in both channels, working our way up from the lower-shelves in retail, meanwhile targeting high-end stores and restaurants with great, yet still affordable wines. And well over the 30-40 pounds price you mentioned, since the cellar price is 10 to 15 euros, generally, and can go up to 25-30 euros. But higher-quality wines, involving other margins, are more plausible to bring along all kinds of support from the wineries, from sampling to guest sommeliers, from personnel training to printed info and so on.

In this case the next question arises: how are ambassadors for Romanian wine selected to introduce it to consumers on store shelves, in restaurants, or at exhibitions and tastings? Is this initiative supported by winemakers? I’d love to hear about your experiences with this role and any collaborations with wineries and associations, if possible.

M.A.: There are no official ambassadors for Romanian wine at the moment. There may be some who perform roles in international professional organizations, from wine experts to sommeliers, there are wine lovers and wine businesses who try to promote Romanian wine, but that’s it for the moment. The Romanian wine industry must get organized and start acting as soon as possible, with everyone participating – I’d say proportionally with their businesses. I had great experiences with the partners of WinesOfRomania.com, the platform – and so much more – I founded almost two and a half years ago.

Romania’s wine industry faces challenges due to the absence of a state-backed and influential marketing body to promote the country’s unique grape varieties and rich winemaking history globally. Personalities like yourself play a crucial role in promoting Romanian wines. In 2021, you achieved a significant milestone by earning your PhD in Marketing. Your expertise is valued for crafting innovative strategies, distinctive communications, and organizing exceptional events. Can you tell us at least briefly about the brightest and most successful? In particular, about your recently published book, which is also a marketing tool.

M.A.: There were several great moments, from the tasting we had with Carrefour Romania in New York, on New Year’s Eve to having the entire jury of Mundus Vini in a tasting of Romanian wines. And then there were fairs, exhibitions and diplomatic events where Romanian wines were very appreciated indeed. But I think that better moments are yet to come and my promise is not to rest until the Romanian wine doesn’t gain the recognition it deserves.

As for the latest book – The Relationship between Country Brand and the Romanian Wine Brand. A heterodox approach – this was the coronation of my studies and is, in fact, the abridged version of my PhD thesis. It is an instrument I made available for all wine producers who try to understand how, why and how long it would take for Romanian wine to gain recognition. I hope it is translated soon, because I think that it is also an academic instrument that can also help other emerging wine producing countries, like the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Albania and others.

How did the idea for RO-Wine, The International Wine Festival of Romania, one of your famous events, come about? What are its dynamics – quantitative and qualitative? What are the future plans?

M.A.: At first it was the idea that Romanian wines would prove themselves best by being put next to international wines, on the same or a higher price level. So, inspired by the fairs and exhibitions I have seen around the world, I decided to present absolutely all the wineries in the same manner – same size booths, same advertising, same amount of wines to be sampled. The results were great and I believe that the first goal was achieved – Romanian producers really are on the same level as new and old producers from both the Old and the New World.

In time, the festival grew, now it is already a tradition to hold an annual edition in the heart of Transylvania, in Cluj Napoca, and I think it turned more into an instrument to educate the general consumers and a place where wine lovers get to discover new trends, new wines, new labels and sometimes even new wineries.

They say wine-growing Romania is full of amazing personal stories. Iconic landmarks like the Jidvei winery, or wineries owned by descendants of Romanian royalty, are a marketer’s paradise. However, there’s a prevalent view that Romanians need to invest more in marketing and communications to achieve greater success. Is it solely about financial investment? What strategies would you recommend?

M.A.: Yes, it is mostly about financial investments, I’d say money would solve 80% of the problems. But it is also about getting the producers to work together and – very important – to agree on targets. Because if one of them wants to promote Romanian wines in Germany, another one in Belgium, two aim at South America and another to Japan, we’re going nowhere. Before communicating, data gathering is crucial, opportunities must be analyzed and weighed, strategies must be put into place. There are many steps to take before jumping on the export train and mindless spending can lead to disasters. We must start with a serious SWOT analysis, do the math, gather the resources and only then start the campaign. It’s a long and tedious path, but there are signs that some things are starting to happen in the Wine Producers and Exporters’ Association. WinesOfRomania.com and RO-Wine, myself and my team will make all our resources available, in case we are presented with a credible plan.

The Wine Travel Awards, now entering its fourth season, was conceived by our media group to promote wine and alcohol brands through wine tourism. For countries like Romania, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, or Armenia, whose winemaking traditions hark back to the Old World, wine tourism presents a powerful tool to capture the hearts of wine enthusiasts and gain international recognition. Despite the old-school connotations of the term “Old World,” these regions boast a wealth of small wineries that dominate the market quantitatively. In Romania, for instance, reports indicate that out of nearly 250 commercial wineries, around 40 are equipped to support wine tourism. This growth is mirrored by the increasing number of travel agencies offering wine tours to both Romanian and foreign tourists. How widespread are such collaborations, are there statistics on wine tourism in Romania? How do you personally see the role of wine tourism in the promotion of Romanian wines? Any thoughts on how the Wine Travel Awards, together with you, could contribute to this in the future (perhaps some ideas for press tours, conferences in different formats, art or food festivals)?

M.A.: 40 wineries offering accommodation may not seem a lot, but there were less than 20 years ago and maybe less than 10, fifteen years ago. The priorities were different in the years since the reinvention of Romanian wine. First was to replant the vineyards, then to bring the wineries to modern standards. And then we had to rediscover everything, including the true potential of our local grape varieties.

So yes, wine tourism is in its youth, but it’s growing fast. The wineries that did not invest in their own accommodation facilities usually collaborate with local guest houses and resorts, the Dealu Mare region, which starts where the speedway ends, sees a fast growth in the amount of resorts, hotels and guesthouses, so we’re on the right track. And this type of tourism will have a significant influence on the way both Romanians and foreign tourists see Romanian wine.

As for the last question – yes, a press tour is a great idea. Art and food may have to wait until a central or local organization gets involved, but I think the time is near. Happy to build the future with your support!

⇒ WTA Files

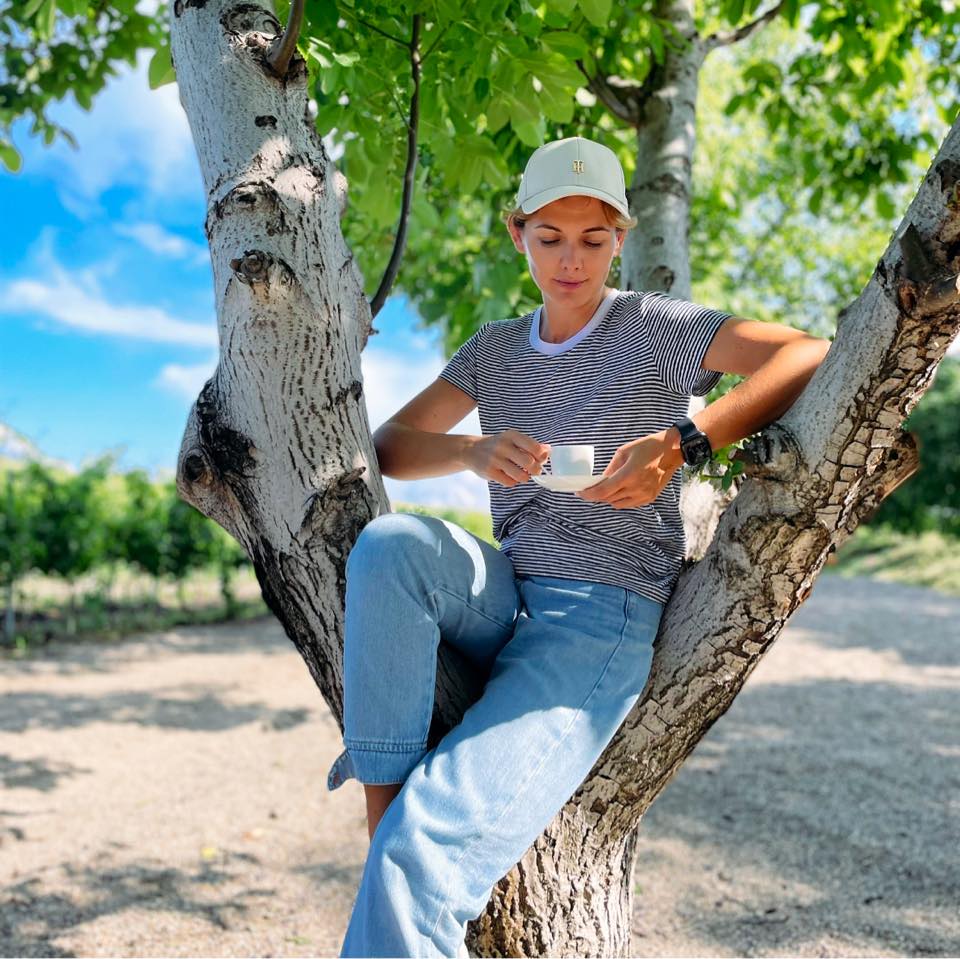

Marinela Ardelean is an executive MBA and PhD in Marketing. Despite growing up in the stunning Maramures region in Transylvania, her passion for wine and spirits blossomed during her time in Italy, now her second home. Her notable achievements include the prestigious title of Dame Chevalier in the Ordre des Coteaux de Champagne and selection by the Italian Chef Academy to lead courses in sensory analysis and wine and food pairings. Her collaborations with the industry’s best further solidify her standing in the global arena. Serving as a driving force for Romanian wines, Marinela actively enhances their reputation and contributes to their equitable positioning among Europe’s elite.

It is an honor for the Drinks+ Media Group to have Marinela Ardelean at the Wine Travel Awards community moreover she become the winner in the 2023-2024 season of the Wine & Food Influencer nomination in the Expert Opinion category.