Bertani on Crafting the Next Generation of Amarone and Elevating Valpolicella’s Identity

Author: Veronika Busel

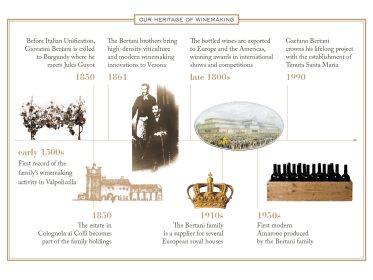

Tenuta Santa Maria’s story unfolds in the rolling hills of Valpolicella, where the Bertani family’s winemaking heritage stretches back nearly five centuries, from early records in the 1500s to the official founding in 1735. At its heart stands the 18th-century Villa Mosconi Bertani, a timeless symbol of tradition and artistry. Across generations, the family has preserved and refined their craft, producing wines that capture both the character of the land and the spirit of innovation. Today, Tenuta Santa Maria presents a portfolio that includes classic Valpolicella expressions as well as rare appassimento bottlings, each reflecting the dedication and vision carried forward by Giovanni and Guglielmo Bertani. To delve deeper into this heritage and the family’s path toward the future, Veronika Busel, Head of Operations at Wine Travel Awards, sat down with Giovanni Bertani for an insightful conversation.

Veronika Busel: Giovanni, the story of your family is deeply intertwined with the evolution of Valpolicella and Amarone. How do you see this long-standing legacy – spanning centuries – reflected in the work you and your brother continue today?

Giovanni Bertani: Our connection to wine goes back much further than many people realize. The earliest document we’ve found dates to the late 1500s – a contract discovered just a few kilometers from Villa di Negrar mentioning grapes, vineyards, and wine. It’s like the first quiet whisper of our family’s involvement in winemaking, so in a way, wine has always been in our blood.

But 1735 is truly a special year for us – it’s when the winery (Editor’s Note: Estate in Arbizzano di Negrar) that stands today was built. That date is like a cornerstone where history crystallizes into the Bertani identity we know now. While our roots are much older, that’s the year the estate as it exists was born.

Our family’s role in the history of Valpolicella goes beyond winemaking. In the 1800s, part of the family was even exiled to Burgundy for a few years, which must have been an eye-opening experience. When they returned, Giovanni Bertani – who shared our family name – was not only a winemaker but also a political figure. He played a major role in shaping the Italian wine industry, helping to organize the second Oenological Congress in Verona, following the first one held in Turin. Our family helped found one of the earliest wine producers’ associations – the precursor to today’s Valpolicella consortium that defines the region’s identity.

That same Giovanni Bertani worked closely with the Ministry of Agriculture to draft the very first Italian wine production regulations. We exported to over 30 countries, which was remarkable for that era.

Regarding our estate, Tenuta Santa Maria, which we have owned since just after World War II – the main building itself has a long history, dating back to the 1300s when it was a monastery. This layered history speaks to the deep roots we have in this land.

Over generations, our family has remained devoted to protecting its independence and to expressing the authenticity of Valpolicella through wines crafted only from our own estate-grown grapes. This approach reflects a deliberate choice: to focus on quality over scale, on tradition strengthened by innovation, and on honoring the land that has sustained us for centuries. Today, Tenuta Santa Maria embodies nearly five hundred years of heritage, passion, and resilience – a story of dedication that continues to unfold with every vintage.

V.В.: You currently offer ten labels. Is there one that stands out as especially significant in reflecting your family’s legacy or a unique approach to winemaking?

G.B.: Among the nine, one truly embodies our heritage: a special release we call the 1928 Acinaticum. It’s our oldest vintage, introduced to the public just this year. This wine predates modern Amarone – it’s crafted in an appassimento style and retains a sweet profile, unlike the dry Amarone we know today. It’s what we consider the “father” of Amarone.

This wine is produced in very limited quantities and reserved for VIP clients and collectors (Editor’s Note: It is also available online.) You’ll find it listed in some of Verona’s most exclusive restaurants for about €10,000 per bottle. It’s not just a wine – it’s a piece of history.

V.B.: What is the scale of your current production across the nine labels? And in terms of market strategy, could you elaborate on your export focus and what defines your approach as a niche, premium winery?

G.B.: At the moment, we produce approximately 300,000 bottles annually, and our goal is to increase that to over 400,000 in the coming years. All our wines come from estate-grown grapes, which gives us full control over quality and consistency. We’re deeply committed to remaining a niche winery – focused on premium quality rather than high volume. That’s reflected not just in how we produce wine, but also in how we bring it to market. We don’t sell to supermarkets at all. Our entire distribution is dedicated to the HoReCa channel – hotels, restaurants, catering – and high-end wine shops that understand and value what we do.

In terms of markets, about 75 to 80 percent of our production is exported, depending on the year and the vintage. Our main export destinations are divided roughly into thirds: Europe, North America, and Asia. The United States and China are our two largest individual export markets. That said, there’s currently some uncertainty – tariffs and shifting global dynamics are affecting the outlook, so we’re monitoring how the market will evolve in the next 6 to 12 months.

Domestically, Italy accounts for about 15 to 20 percent of our sales. That’s actually quite typical for wineries like ours in Italy, especially newer or family-driven ones focused on quality and international visibility.

After World War II, my father played a vital role in bringing Amarone to the world stage – particularly in the United States. He traveled extensively, personally introducing the wine abroad, while the rest of the family worked on strengthening the winery’s heritage at home.

Our philosophy has always been to push Valpolicella towards greater elegance and authenticity – wines that truly express their origin and craftsmanship. Every bottle is estate-grown – something that’s increasingly rare today. Many big producers bottle wines made from grapes they don’t own, losing that close connection between vineyard and bottle. That’s not how we work.

In terms of scale, we’re quite small. We are boutique, selective, and dedicated above all to quality.

V.B.: I’ve noticed Bertani doesn’t really highlight a specific oenologist. Is that a deliberate choice – to emphasize the family over an individual winemaker?

G.B.: Yes, absolutely – that’s very much our approach. Bertani has always been family-run, and it’s the family that shapes the style of the wines, not any one winemaker. Of course, we work closely with talented winemakers—they’re an essential part of the team – but it’s a collective effort. Currently, we collaborate with Luca Rettondini, based in Tuscany. But building the brand identity around a single individual is something we avoid. That’s more typical of modern, investor-owned wineries where a winemaker is brought in to define the style. For us, it’s different.

The family is hands-on at every step, from vineyard to bottle. My father was instrumental in shaping our identity, and now my brother and I carry on that legacy. We’re all trained in wine ourselves, in many ways acting as oenologists. But beyond the family, there’s a continuous process: agronomists contribute, we hold regular blind tastings, and research guides us as we evolve the wines carefully.

A good example is our unique Corvina clone, developed by my father decades ago. This clone grows only on our estate and now makes up 60% of our Amarone. It gives the wine a distinct character – more raspberry and strawberry notes rather than the usual cherry typical of other Corvinas. This wasn’t a winemaker’s whim – it was a long-term family project.

In recent years, we’ve also reintroduced nearly forgotten indigenous varietals, working with a nonprofit. Today, we use around 19 permitted varietals in our wines – a story you can explore further on our website.

So yes, the winemaker’s role is important, but they don’t solely define the wine. We believe wine culture should be shared across the entire organization, not focused on one person. In investor-owned wineries, winemakers and CEOs often come and go, and the style shifts with them. That’s not what we want. Our goal is to preserve and refine, not reinvent. Our Amarone still follows the same guiding vision from the 1950s: drier, more elegant, with less residual sugar. The details evolve, but the philosophy remains.

V.B.: In our conversation, you mentioned that your family took an unusual path when it came to replanting vineyards, avoiding the standard practice of relying on commercial clones. Could you explain what that meant in practice, and how it shaped the identity of your wines?

G.B.: Absolutely. At a time when most wineries were replanting and, in the process, losing biodiversity – and with it, their identity – my father realized that this approach carried risks. Back in the 1980s, the market offered only a handful of commercially available clones, designed primarily for yield or drying efficiency. Choosing from those meant reducing a region’s complex landscape into just a few generic profiles. The result was that wines across different producers started tasting increasingly similar, and the richness of native diversity was being lost. My father wanted a different path. When he faced the need to replant, he chose not to rely on those commercial clones. Instead, he believed that if we wanted our wines to carry our own voice – not just a generic “Amarone accent” – we had to start with the material already thriving in our vineyards. That’s when he began collaborating with specialists in France who shared his vision of precision and genetic heritage. The method we used is called massal selection. Rather than buying new plants, we walked our oldest vineyards row by row, vine by vine, looking for individual vines that stood out for their balance, the way they ripened, their cluster structure, or their aromatic expression. We tagged those vines and collected wood samples. These were grafted onto rootstock and cultivated under monitored conditions, with their development tracked over several years: performance in different soils, disease resistance, flavor, and phenolic profile. It was a slow and meticulous process. Eventually, we identified two or three biotypes that truly represented the DNA of our land. These aren’t commercial clones – they’re unique to us, carrying the fingerprint of our family and vineyards. The impact was remarkable. Our wines became more consistent, yes, but more importantly, more alive. They gained clarity in expressing the site, the altitude, and the season. That gave us the foundation to build a real, distinctive identity.

We tagged them and took wood samples from those individual vines. Then we worked with the nursery, which grafted them onto rootstock and grew them under monitored conditions. Over several years, they analyzed their development – how they performed in different soils, their disease resistance, but especially their flavor and phenolic profile. It’s a slow process.

Eventually, we settled on two or three key biotypes that expressed what we considered to be the DNA of our land. These are not commercial clones. They’re our clones. You won’t find them elsewhere. That’s why I say that even the plant material in our vineyards carries our family’s fingerprint.

The impact? Profound. The wines are more consistent, yes – but more than that, they’re more alive. There’s a clarity in how they speak of the site, the altitude, the season. It gave us a foundation we could build a real identity on.

V.B.: You’ve highlighted the importance of precision and heritage. How do you balance tradition with innovation? Is there room for evolution within such a rooted framework?

G.B.: For us, it’s not about choosing between tradition and innovation – it’s about using innovation to protect and evolve tradition in a meaningful way.

Take drying, for example. One of the decisions we’ve made is to continue using traditional bamboo racks – the arele – for the appassimento process. This year, we’re even investing further by building more of them. Almost no one uses bamboo anymore – maybe 2% of Amarone producers still do. Most have switched to plastic crates and controlled humidity systems. But we don’t use any machine drying or humidity control. For us, this manual, natural method is essential – it defines a specific drying profile, a specific identity that connects our wines to a heritage that’s disappearing.

Another key decision is how we approach aging. Legally, you can produce Amarone without any oak aging at all – aging it in stainless steel or concrete is allowed. But we’ve chosen to age all our Amarone as Riserva. That means a minimum of four years by regulation, but we typically go to five, sometimes six. And we age only in large-format casks. That’s traditional – but at the same time, we apply innovation: we monitor oxygen ingress, conduct micro-vinifications to experiment with different oak sources, and work with coopers to fine-tune toasting levels. So we’re not trying to change the style – we’re refining it through knowledge and detail.

We also harvest much earlier than many others – typically at the end of August or early September. Most wineries are still harvesting in October. But climate change has shifted everything. Sugar is no longer the issue – it’s phenolic ripeness and acidity. Harvesting early allows us to preserve freshness and vibrancy in the grapes, which ultimately gives us a more elegant, more subtle Amarone.

In the vineyard, we’ve started implementing regenerative practices — more cover crops, less tilling, the creation of biodiversity corridors. And we’re trialing dry farming in some plots to encourage deeper root growth, which we believe will enhance the expression of minerality in the wine.

So yes, we innovate. But every choice – from vineyard selection to natural drying to extended aging – is made in service of preserving and amplifying a specific identity. We’re not interested in shortcuts. Amarone, the way we see it, should reflect a continuity with the wine’s origins in the 1950s. The wines should be consistent, yes, but also alive – capable of evolving while staying rooted in something real.

V.B.: Let’s talk about family dynamics. With different personalities and philosophies in a family, how do you make important decisions – especially those that shape the style and direction of your wines? Is there a structured process, or is it more intuitive and collaborative?

G.B.: Personally, I find blind tastings invaluable for alignment. But before diving into that, it’s important to understand what’s been happening regionally.

Verona has produced wine at scale since the 1890s – it’s a very productive, successful region. Amarone evolved from a niche, exclusive wine into a mass-produced style. With that growth, the region began to be seen less as terroir-driven and more as a stylistic category.

Transparency has suffered. Ask a new-generation sommelier today about Amarone and often they won’t know the precise vineyard origin or production details. Amarone is reduced to a “style,” often perceived as heavy, sweet, even clumsy.

So after losing our father three years ago, our family felt a strong urge to reconnect with our roots and terroir. It’s an ongoing journey of experimentation and discovery – even for us.

Decisions like replanting vineyards or investing in equipment are made collaboratively. We bring together perspectives from the winemaker, agronomist, and family, and blind tastings are key to that process. These tastings aren’t private – they’re part of our regular team discussions. Sometimes we vote, sometimes we debate, but we always aim for consensus and stay focused on our shared goal: making wines that reflect our terroir and carry forward the Bertani legacy.

This is something you can do because you’re a boutique winery. If you were producing for large-scale distribution – like for supermarkets or monopolies, where everything is price-driven – you wouldn’t have the luxury to work at this level of detail. You’d have to focus on consistency, low cost, and standardization, making wines as inexpensive as possible.

So yes, we are fortunate to be estate-grown, focused on single-vineyard expressions, and positioned in the premium segment – which gives us the freedom to work this way, with deep attention to terroir and detail.

V.B.: You mentioned evolution and experimentation. What do you see as the next step in Amarone’s evolution? Where is it heading?

G.B.: I believe the future is about transparency, terroir, and connecting people to a specific vineyard and method. It’s not about selling a generic brand.

We’re thinking about Amarone not as a fixed stylistic category, but as something that can evolve while remaining authentic. For example, we’re now exploring the use of amphorae for Amarone aging or fermentation — but not the typical terracotta amphorae associated with orange wines. These are very thin, porous vessels made by a company called Tava in Alto Adige. They allow for very controlled oxidation, which is completely different from traditional terracotta used in ancient winemaking.

This could be an opportunity because you can age or ferment wines in a container with oxygen exchange similar to wood barrels – but without imparting any wood aromas. This idea actually came from our winemaker, who had seen it used in Tuscany.

By the way, Tava sells about 80% of its production to Bordeaux – many châteaux are now using these amphorae instead of oak barrels.

So this is a perfect example of how we can adopt new technologies not to mimic trends, but to better express our own terroir, varietals, and organic characteristics in a purer way. It’s not change for the sake of change – it’s about refining identity.

V.B.: Beyond Amarone, how do you position the rest of your wine portfolio and other aspects of the business? What role do these play in your identity as a winery, and how do you want them to be perceived by the world?

G.B.: We’re not strictly an Amarone producer, though Amarone is of course central to our story. We also produce wines that allow us to showcase the diversity of our region beyond the traditional Valpolicella image. For example, we have a Cabernet-Merlot blend planted by my father in the early ’90s, with production starting in 2000.

These wines are more niche and not always easy to introduce, especially in markets where Verona is seen exclusively through the lens of Amarone, Ripasso, and Valpolicella. But once people connect with our brand and gain trust in what we do, they start to explore the rest of the portfolio, and that’s when these unique expressions really gain recognition.

Beyond the wines themselves, we also see hospitality as a key pillar of our identity. Our next step is likely opening a restaurant on the estate. It’s about creating deeper connections with people, bringing them closer to the land, the food, and the wines – offering a complete experience that reflects who we are and where we come from.

V.B.: Looking ahead to the next decade, how do you and your brother define the winery’s strategic direction and priorities? Do you have a clear mission or positioning that guides your decisions?

G.B.: For us, the mission is to become the true reference point for Valpolicella – a benchmark defined by authenticity and respect for terroir, not volume or broad market trends. While many larger producers rely on IGT wines sourced outside the Valpolicella zone, diluting the region’s identity, we move firmly in the opposite direction. We invest heavily in indigenous varietals, micro-vinification, and single-vineyard expressions to highlight the unique character of our land and clone of Corvina.

Verona’s native grapes hold enormous untapped potential, and we want our wines to be recognized for elegance and refinement rather than heaviness or industrial style. For example, our Amarone has around two grams of residual sugar – well below the regulatory limit – favoring a fruit-forward, food-friendly style that challenges Amarone’s typical perception as overpowering.

Our strategy revolves around preserving traditional practices – like natural drying, long aging, and selecting indigenous yeasts – and rejecting industrial shortcuts. Transparency and clear communication are also key; we want consumers to understand and appreciate the depth and authenticity behind every bottle. In essence, the next ten years are about deepening roots, honoring tradition, and elevating Valpolicella’s true identity on the global stage.

V.B.: Do you think there’s a chance for Valpolicella to establish more sub-regions in the future?

G.B.: There is actually an ongoing discussion about creating eight sub-regions within Valpolicella. They’re discussing an update to the current DOC regulations in the region, which would introduce sub-regions encompassing around 80 different villages. They’re talking about updating the current DOC regulations to reflect this.

The idea is to define eight formal sub-zones – five in the Classico area and three in the expanded area. If this happens, it would allow us, for the first time, to officially register and recognize single vineyards within those sub-regions. That would be a big step forward in terms of transparency, traceability, and elevating the identity of each unique terroir.

You will be able to call your Amarone with the name of the village. And if you do that, you will need to register a single vineyard. And there would be more requirements – like a lower yield, a more precise process. The current process for Amarone doesn’t actually require any longer aging. But in the future, if you want to have this level of precision, there will be mandatory regulations. There will be a much lower yield from the vineyard.

The way we work today, all our production would basically fit within this new regulation. Today – funny enough, or actually, I think it’s pretty sad – if I want to put the name “Negrar di Valpolicella – Arbizzano,” where we are based, on the label, it’s not allowed by regulation. It’s not accepted.

So I have to stick with the generic name “Amarone Classico,” for the whole region. There is no specificity. There is no regulation that helps me connect the wine to a specific area or sub-region. So finally, there is a discussion within the consortium, among producers, and we are working on developing this new regulation. We are discussing how to introduce this kind of separation.

As I was mentioning before, Verona is not actually a style of wine. It is a region with specific terroirs. So the region will have to clarify the understanding of Verona wines very soon – this will be a crucial step that redefines the future and elevates the wines’ standing on the global stage.

V.B.: How significant is the impact of climate change on Verona’s wine production? To what extent are changes in temperature or other environmental factors influencing your viticultural practices and long-term planning? Is this already noticeable in the region?

G.B.: It’s totally here. So what happened is that – even as I was mentioning before – we used to harvest at the end of September or beginning of October. Today, we mostly begin at the end of August. The harvest has already shifted by about a month since the 1970s, I would say.

And what’s helping us is two things. First, we have a blend of 18 or 19 indigenous varietals. Some varietals that were considered too acidic years ago – like Oseleta (Editor’s note: Oseleta is a rare, autochthonous red wine grape variety from the Valpolicella area in the Veneto region of Italy – more details on the Tenuta Santa Maria website) – were too acidic in the ’70s, not very interesting, didn’t mature enough. But today, they’re actually helping us a lot in rebalancing the blend – bringing freshness, acidity, and really interesting tannins. These are useful especially when we see over-maturation or concentration due to climate change and warming.

So, the first strategy is changing the blend and relying on indigenous varietals to rebalance the style of the wines.

A second option is playing with different elevations in the region. We basically start from about 50 meters – the lowest part of Valpolicella – up to 600 meters. So there’s a huge difference in elevation that you can work with.

Our next project is in the third valley, where we will grow grapes at about 300 to 400 meters. Currently, we are at around 180 meters here. So bringing the vineyards to higher elevations – positions where, back in the 1970s or 60s, you couldn’t achieve proper ripeness – is now an opportunity.

Today, those elevations are helping us produce wines that are more subtle, with more acidity and elegance. So yes, climate change is totally affecting us. But we are lucky as a region, because this blend of varietals helps a lot. And the elevation options help, too.

If you go to a region like Bordeaux, where it’s flatland and you don’t have much variation in elevation, you can’t play with that.

V.B.: The estate Tenuta Santa Maria clearly carries a special atmosphere – with its poetic, aristocratic heritage. How does that identity shape the kind of experiences you offer today? Who are the people coming to the estate, and how do you position what they find here? Are you focused on the premium segment, or is it something different?

G.B.: For us, wine tourism isn’t just about luxury or income – it’s about culture. We’re looking for curious, independent travelers who see wine as a deeper experience, not just a drink. They want to understand the history, the process, and the soul of a place.

Of course, we offer premium tastings – like our Amarone vertical going back to 1928 – but our core audience is made up of passionate individuals, not tour groups. About 95% of our visitors come independently. They’re here for something authentic.

The estate Tenuta Santa Maria offers that: an estate rich in poetry, heritage, and history. This is one of the original homes of Amarone. And we try to share that with people – not through grand gestures, but through storytelling, education, and emotional connection.

During tastings, we use visuals and narratives to explain everything: the grapes, the land, the drying process, fermentation. It’s not about saying “this is the best wine,” but about helping people understand why it matters.

Our team is highly educated and well-prepared, but we keep the tone light and welcoming. That balance helps guests feel at ease while also giving them a deeper understanding of what they’re tasting and experiencing.

That’s what creates a meaningful experience. We aim to offer a different kind of luxury – one rooted in time, care, and cultural depth. Guests leave knowing how Amarone is made, what makes this region special, and often with a new appreciation for it all.

That’s been a key point in the way we’ve developed our experiences here and why they’ve been so successful.

V.B.: Could you share a memorable story or experience from Tenuta Santa Maria that captures the spirit of your hospitality and the unique atmosphere you aim to create for your visitors?

G.B.: So many things… I have to think about it.. What usually happens is that I try – when I can, if I have the time – to meet the groups and interact with them personally. And what I often hear as feedback is that when people come here, they really feel the passion of everyone working with us. They feel the hospitality.

There’s this strong sense of personal involvement. Everything I’ve described to you – these details, this care – it’s because we are truly passionate and connected to what we do. And you can’t go into this level of detail without that kind of connection.

The compliments we receive often mention this feeling – that there’s something personal, almost a different world. And that translates into everything we create and develop.

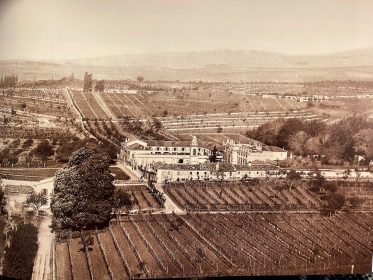

When our visitors take the final turn on the road and see the vineyards, the estate – with its buildings preserved since the 1700s – the attention to heritage and detail… the passion behind all of it. What they usually tell me is that it’s like stepping 300 years into the past.

They arrive and, for a moment, feel almost disoriented – as if they’ve stepped into another era.

We don’t notice it ourselves, because we live in it every day. But when we meet people, we realize it – how unique this environment is.

And that’s why these interactions are so important to us. They reinforce our mission going forward.

There’s something here… the “genius loci,” as they call it – the spirit of the place. There is a soul living on the property, and we have a responsibility to preserve that.

To go even deeper – understand more about what this place was, and what we can bring forward to make it even more unique. Because, in many businesses, those things get lost over time. And we’re doing everything we can to avoid that.

Stay connected with Wine Travel Awards:

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/WineTravelAwards/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/winetravelawards

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/winetravelawards/